Soft Power and Sacred Futures: Kerry James Marshall’s Diasporic Vision

Undoubtedly long overdue, Kerry James Marshall’s The Histories at the Royal Academy of Art is an incredibly moving, all-encompassing, and hugely ambitious retrospective. This is the largest showing of any African-American painter ever displayed in Europe, and its effect has been evident. In what has proved an exceedingly unifying, and even healing, show amongst the Black artistic community in London, many have found themselves making several returns, including myself. Marshall has spent his whole career rewriting and reimagining depictions of Black figures throughout history in spaces where they were often excluded, as well as in scenes of community, striking an intimate balance between moments of joy, softness and quiet power. With works spanning from as early as the 1980s to as recently as this year. Marshall’s brilliance is illuminated in the complex compositions of his canvases. A hallmark of his work is his command of our shifting gaze, allowing us to find various references, imbuing them with a meaning so layered that it demands that stereotypical head-tilted-chin-scratched-stare at the canvas that all so-called ‘serious’ art lovers do.

An important conversation within diasporic communities is our disconnect and subsequent demonisation of traditional African spirituality practices, deities and symbolism. A remnant of colonisation, this demonisation of this historic practice is something that Marshall vehemently refutes. We see this emerge throughout. Could This Be Love (1992) offers a glimpse into Marshall’s understanding of the marriage between love and spirituality. Pictured in the intimate setting of one’s bedroom, a couple are seen undressing, though the exact intimacy of their gestures remains deliberately ambiguous. With nods to La Venus Negra – the enduring goddess of black femininity, whose self-affirmative nature is emboldened in beauty, sensuality and freedom from the white gaze – the painting features a sacred, candle-lit altar and lyrics detailing the complexities of having multiple lovers – yes, plural. The work presents a striking vision of the divinity in the Black woman, but also a keen and playful erotic confidence. Marshall repeatedly uses lyrics symbolically, adding layers of meaning and context to the worlds his figures inhabit. In this domestic setting, we see Marshall bring spirituality into the everyday. It becomes a practice that can live in bedrooms and between lovers, flowing naturally through ordinary moments. Marshall doesn’t ask us to radically reimagine these spaces; rather, he intentionally expands them, showing that our spirituality is ancient and to be lived in the details of daily life.

Kerry James Marshall, Could This Be Love, 1992. Acrylic and collage on canvas, 261.6 × 289.6 cm. Pinault Collection, Paris. © Kerry James Marshall. Photo: Maxime Verret

Marshall deepens his exploration of African spirituality in his paintings of the Middle Passage. Despite marking an incredibly distressing and traumatic moment in Black history, Marshall paints these scenes in such a way that feels like a gentle invitation to unpack such weighty imagery. Plunge (1992), awash with vibrant blue seas, makes a subtle nod to Haitian spirituality, featuring a boat named Immamou – a mythical ship captained by Agwe, the Voudou spirit of the sea and deity to fisherman. This spiritual framing continues in Terra Incognita (1992), where Marshall uses the figure of a waiter to represent Eshu-Elegba, the Yoruba deity of crossroads and change, alongside a boat voyaging across the seas. In this context, Eshu-Elegba is depicted as a guide through the Middle Passage – a spiritual intermediary protecting enslaved Africans along their treacherous journey. Throughout the exhibition, Marshall’s forensic understanding of Black histories acts as the compass guiding his work, resulting in paintings that are at once imaginative, referential, and seemingly effortless.

Kerry James Marshall, Terra Incognita, 1992. Acrylic, ink and paper collage laid on canvas with metal grommets, 239.4 × 189.5 cm. Private collection. © Kerry James Marshall. Image courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Importantly, Marshall also reimagines venerated political figures whose violent colonial pasts are often santised by an agreed-upon PR version of events. In Portrait of Nat Turner with the Head of His Master (2011), we see Nat Turner, leader of a slave rebellion, standing boldly as he wields a bloodied axe and the severed head of his white master haunts in the background. Yet, Marshall invites us to reframe this historical moment in which the sitter becomes at once a figure of black freedom, social mobility, and indeed violence. In doing so, he paints for an alternative gaze, subverting what has often been framed as a moment of terror and savagery into a watershed moment in the history of Black liberation.

Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of Nat Turner with the Head of His Master, 2011. Acrylic on PVC panel, 91.4 × 74.9 cm. Private collection, Courtesy David Zwirner. © Kerry James Marshall. © Kerry James Marshall. Image courtesy David Zwirner, London. Photo: Kerry McFate

This inversion continues in Marshall’s depictions of political authority, where presidential figures, such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, are painted in a distorted manner. Painting these founding fathers of America on their respective estates, built on the backs of slaves, Marshall mirrors their inflated egos with elongated stretched heads placed on small and disproportionate bodies. Through his daring representations of these historically significant figures, he calls us to question the establishment and its history with both our curiosity and cynicism equally intact.

Although the exhibition is titled Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Marshall’s work extends beyond temporal boundaries, viewing history both in retrospect and as endlessly unfolding. In a world where our current reality is in constant flux and increasing uncertainty, Marshall’s world-building potential becomes increasingly poignant. Certainly, for our friends across the pond, amidst the rise of fascism and far-right policies, his work proposes an alternate possibility that, through its sense of hope and optimism, insists on Black futurity as a form of visual resistance.

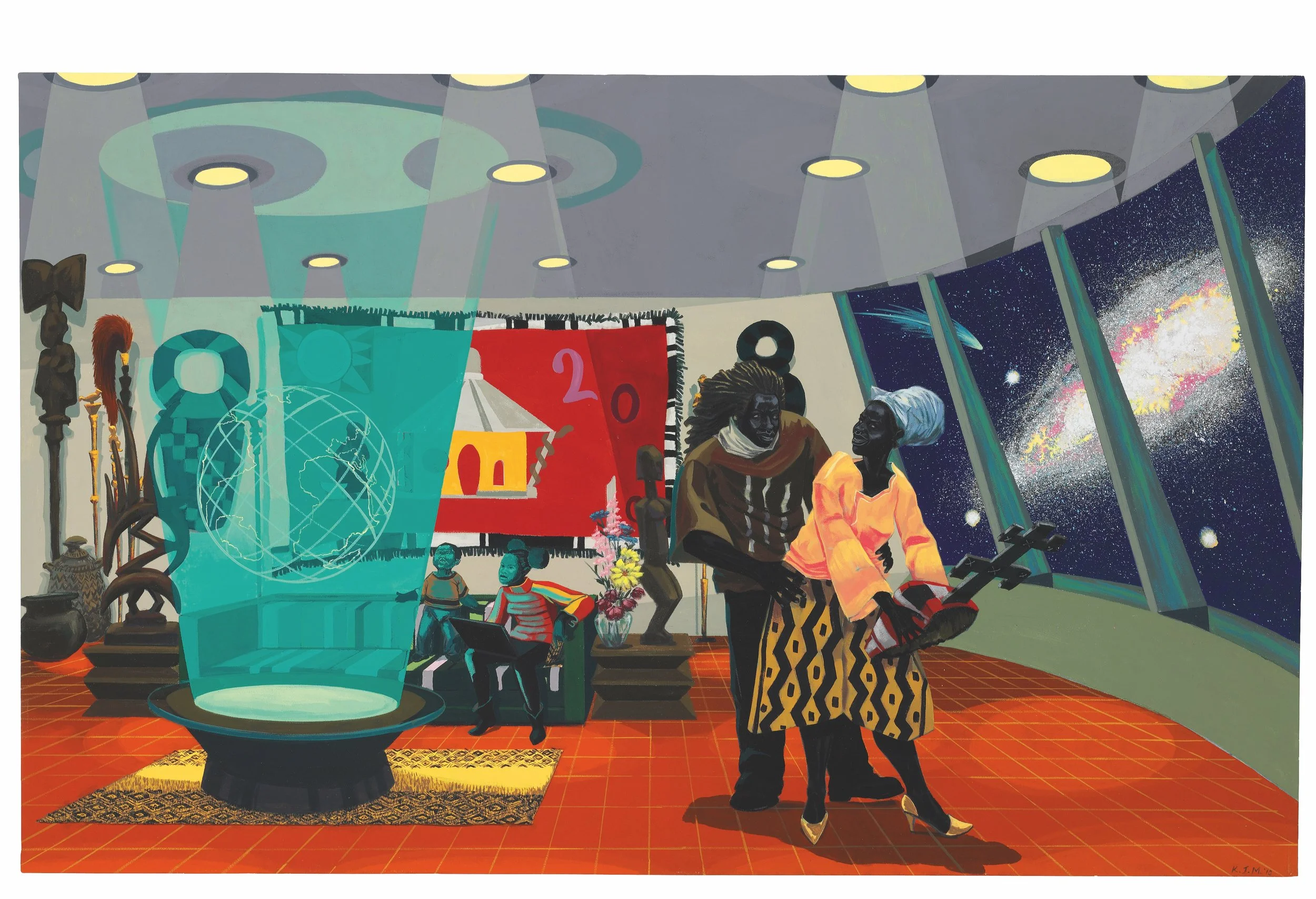

How, then, might we as a people begin to map our futures, one step at a time, through the power of art? That old adage that “you must see to achieve” feels especially true here. Marshall’s sight is sharp and exacting. In Keeping the Culture (2010), he depicts an Afrofuturist household with a view of the cosmos out the window, children looking at a projected holographic image of earth, and a couple embracing in the fore, all anchored by traditional Yoruba sculptures which linger in the background. Here, history and the future collide, providing a look into our potential that is both familiar and invigorating.

Kerry James Marshall, Keeping the Culture, 2010. Oil on board, 76.2 × 121.9 cm. Private collection. © Kerry James Marshall. Photo: Christie’s

Notably, Marshall’s ability to unearth subdued histories of violence and oppression exposes the unavoidable legacy of British colonialism which haunts the Black British diaspora. In a national culture that wilfully ignores its violent past and maintains the fiction that we live in a post-racist country, to stand in front of these paintings as a Black British viewer in 2025 is to feel the weight of histories that are repeatedly obscured or misrepresented. As such, his work transcends geographic borders, exploring the transcultural patterns of historical erasure that underpin both American exceptionalism and British imperial nostalgia.

Viewing Marshall’s works in London, the heart of the empire, whilst in the Royal Academy is context that is impossible to ignore throughout the show. At the entrance to the exhibition the work Untitled (Underpainting) (2018) depicts Black school children viewing Marshall’s paintings in a museum. Here, Marshall makes clear that education plays an integral role in building diasporic futures, and that this work begins with children. Beyond the often lack-lustre framing of Black history month here in the UK, which has been criticised for its centring of African-American figures of liberation, his paintings invite us to question the histories we haven’t been taught, and equip the next generation to pursue alternative paths to knowledge.

Kerry James Marshall, Great America, 1994. Acrylic and collage on canvas, 261.6 × 289.6 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Gift of the Collectors Committee, 2011.20.1. © Kerry James Marshall

More than a must-see exhibition, The Histories is one that will certainly be looked back to. Marshall’s chronicles of Black histories act as vital source material to understanding the complexities of our diaspora, divorced from an oppressive white colonial gaze. A titan of contemporary art, he is fastidious in his aim to traverse the vastness of our history and explore what it means to be Black. The show has the ability to move you to tears – which Great America (1994) certainly did for me. The sheer scale and complexity of the works invite you to linger for hours and pore over every golden detail. Prepare to leave the show with several questions, a web of cultural references and a renewed appreciation for the brilliance of Kerry James Marshall.

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories is on until 18 January 2026 at The Royal Academy of Art.

The exhibition is organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in collaboration with the Kunsthaus Zürich and the Musée d'Art Moderne, Paris